The extravaganza takes place in the bathroom. A lady is crooning an ode to the “the only place where I can stay, making faces at my face; a special place where I can stay and cream, and dream.”

A gaggle of gentleman salesmen hang onto every word, erupting in applause.

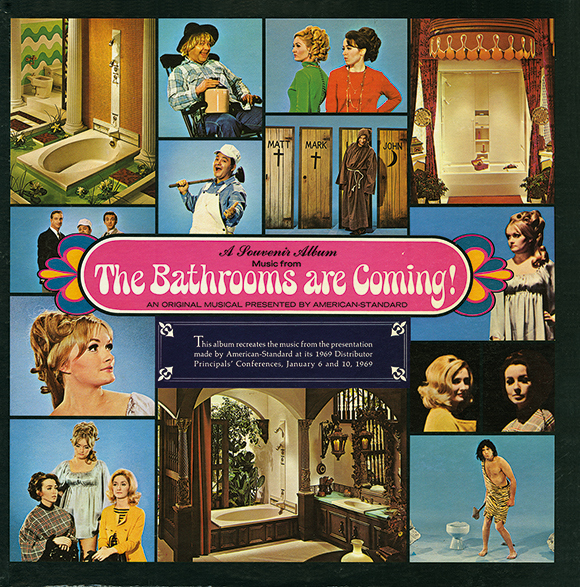

This song, “My Bathroom,” was composed by Sid Siegel and was just one of the inspirational tunes featured in American-Standard’s 1969 stage and video show “The Bathrooms Are Coming!”

Performed at the company’s “Distributor Principles Conferences” in Las Vegas, the musical, as described by Steve Young and Sport Murphy in their book Everything’s Coming Up Profits, involved both a Greek goddess named Femma being “implored… to start a bathroom revolution” and references to a Cornell professor’s research on water closet ergonomics. (Spoiler: The professor’s work was sponsored by American-Standard.)

“The Bathrooms are Coming!” is one example of an industrial musical, an elaborate Broadway-style show that was commonplace at company conferences in the U.S. between the 1940s and 1970s.

When cost wasn’t an impediment, the performances were sometimes recorded, pressed, and distributed as souvenirs to “recreate the magic and reinforce the message back home,” writes Young. Independently, Young and Murphy began collecting the rare vinyl. I recently spoke with Sport Murphy over the phone.

“You start to think, my god, what were these people thinking?” True. “But the absurdity of these things is kind of like their way of bonding. You know: ‘I spend every day trying to convince people to buy this bathroom suite, and here’s this song that turns it into this big, lush cartoon.’ And they appreciated it because it’s something they could all relate to.”

Industrial musicals weren’t merely about camaraderie and a few chuckles. “There was a lot of minutia that had to be crammed into the shows,” says Murphy. “There were catchphrases that had to be hammered into the head of the employees, just like advertising does to the general public.” Songs were important devices for remembering a product’s key new features, like this one from the 1956 GE appliance show “It’s a Great New Line!”

“Ive Got a Wide Range of Features”

Or for improving sales techniques, per this 1959 gem from the Oldsmobile show “Good News About Olds”:

“Don’t Let a Be-Back Get Away”

They were also intended as a steam valve to acknowledge and dissipate on-the-job stress, like this one from 1961′s Coca-Cola show “The Grip of Leadership”:

And to complain about government policy and interference — a not-so-subtle point made by this number from the 1976 Exxon Convention:

Corporate musicals came to fruition in the wake of World War II, when there was a desire for, as Young writes, “lots of stuff, which American corporations were eager to supply.” The performances also arrived on the heels of story-driven shows like Oklahoma!, which debuted on Broadway in 1943. “It’s a genre that Americans associated with class and with prosperity, so that sort of aesthetic gave it its emotional hook” with big companies, Murphy said.

The U.S. was also feeling pretty darned united. “You’re talking about an entire generation that, between the depression and the war, had gotten into the mindset that we really need each other, we trust our leaders,” he explained. “And the least significant person in the organization is as important as the most prominent one.”

Of course, industrial musicals wouldn’t be an American story without enterprising businessmen looking to boost efficiency and increase profits. According to Murphy, the emergence of music in American corporations can be tenuously traced to National Cash Register at the turn of the 20th century and its founder James H. Patterson, who “had this very paternalistic ideal towards his company.” This ranged from creating more humane conditions for his factory workers and providing extensive training to his sales staff to demanding loyalty and exercising a maniacal sense of control, firing people left and right. Part of his strategy included what Murphy calls “pep talk shows.”

“They would show slides, people would sing songs, and they evolved into theatrical productions that were essentially intended to be morale boosters” while hammering home the company ethos and lauding efficiency in the workplace.

Patterson fired a certain Thomas J. Watson, who later went on the lead IBM for more than 40 years. Watson’s IBM also used music as a central component in company culture, perhaps most famously creating this epic songbook in 1935 that includes “Ever Onward,” the official IBM rally song, as well as odes to senior executives set to well-known tunes (listen to four of them here).

Murphy credits IBM’s use of music as a kickstarter for other companies, particularly those like Mary Kay Cosmetics and Fuller Brush Company that relied on salespeople who needed to stay motivated.

More complicated theatrical wonders like “The Bathrooms Are Coming!” were the achievement of ambitious producer Jam Handy. After swimming in two Olympic games (1904 and 1924), Handy became obsessed with the psychology of employee motivation during his time in the Chicago Tribune’s advertising department, says Murphy. This led to his association with James H. Patterson, who became a mentor.

Handy made a good living producing short films for companies like General Electric, Chevrolet, and Coca Cola in the 1930s, and shifted his focus to making military films during World War II. “After the war” writes Murphy, “the consumer boom opened numerous new opportunities for the company as more and more corporations and agencies sought the Jam Handy magic.” By the 1950s, Jam Handy Productions was “the nation’s largest employer of theatrical talent, producing as many as 20 sales conference shows yearly.” Other production companies followed suit. And as more big corporations started embracing the performances they orchestrated, the industrial musical as written about in Everything’s Coming Up Profits was born.

One of the most remarkable aspects of the whole phenomenon is how much money companies pumped into them. Steve Young notes that the first show composer Hank Beebe orchestrated in 1956, for the next year’s Chevy models, had a budget of $3 million, more than the half to three-quarters of a million that was spent on the average Broadway show during the same time period (the high price was largely due to the fact that the entire production bounced from sales conference to sales conference across the country). All shows weren’t necessarily as expensive, however; this 1955 Milwaukee Journal article covers a $250,000 Oldsmobile show that toured for 10 weeks and featured a storyline involving “an Arabian Nights used elephant dealer.”

Oldsmobile told the Journal almost every car dealer across the country saw the show, spreading a consistent message about new products nationwide. “They had a fine time, saw pretty girls and nice scenery and heard good songs and watched expert dances,” writes the article’s author. “But they also got a pretty strong, impressive sales message.” Indeed, most composers hired by companies had some flexibility in the music, but not in the messages themselves.

And while there isn’t hard ROI data on revenue made based on the content of the shows, according to Murphy it made a strange economic sense to those involved: salesmen were (hopefully) motivated to sell more, while actors, musicians, and composers got paid a union wage. Some, like Fiddler on the Roof co-composer Sheldon Harnick, wound up on Broadway.

Things began to fall apart when both business and popular culture changed dramatically between the 1960s and ’90s. For one, the shows struggled to retain their “cool” factor during the ’60s, often lagging a few years behind trends, and making a bit of a mockery of all things mod or psychedelic. “It would be these guys with very obviously long blonde wigs and granny glasses playing really bad simulations of The Birds,” says Murphy. And why would you stage an elaborate show with fake songs when you could just hire a famous musician to perform instead?

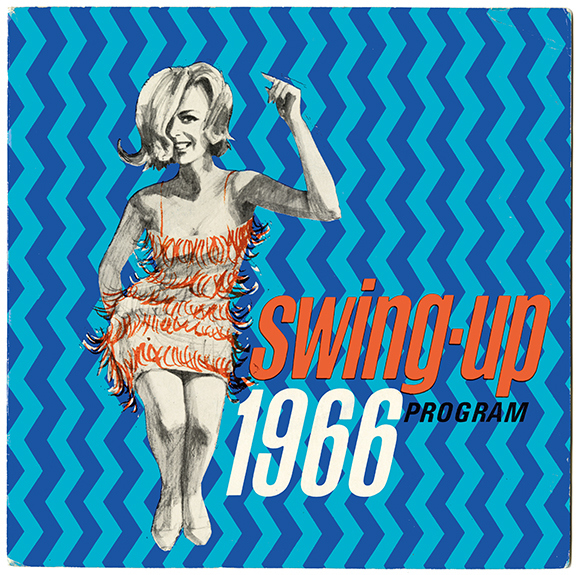

From a 1966 Chrysler Corporation conference, courtesy of Blast Books

From a 1966 Chrysler Corporation conference, courtesy of Blast Books

One can also imagine that the peculiar gender politics of songs like “My Bathroom” were starting to strike the nerves of an increasingly diverse workforce as time inched closer to the turn of the century and sales conferences weren’t merely boys clubs. (Though Mary Kay slowly developed its own quasi-religious conferences, complete with songs, by the 1980s.)

But perhaps the biggest reason industrial musicals crawled into historical oblivion has to do with a change in the employer-employee relationship (not to mention the place of the U.S. economy in the country’s culture).

“It was likely a chicken-or-egg situation,” Murphy theorizes. “The shows probably motivated people, but it was also coming from a corporate culture that felt a sense of belonging. In the bigger corporations, they had a real stake in keeping their employees happy and loyal. They would rather have a lifetime employee who really understood the business and believed in it, rather than a series of revolving door specialists who would come and go.”

In a letter Hank Beebe wrote to Murphy and Young upon the publication of their book, he remarked that the text brought to life “that [era’s] civilization — its extravagance, its confidence, its belief that the future belonged to those who reached for it. Even the belief in the corporation as a force for good comes through, a belief that recent history has not exactly upheld.”

Whether or not you buy into this nostalgia, Thomas J. Watson’s lyrical approach would probably be lost on the IBM of today. As the Washington Post reports, Watson once listed the company’s values in the following order: respect for the employee; a commitment to customer service; and achieving excellence. By 1994, when Louis V. Gerstner Jr. headed the company, he orchestrated an epic turnaround, putting shareholder value and customer satisfaction at the top of the list. Employees and community were at the bottom. The most recent two CEOs placed investor returns at the top of their priority lists.

But I’m sure there’s a song for that somewhere.